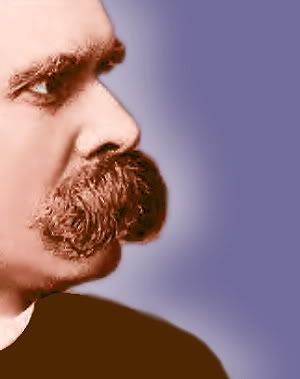

I first discovered Nietzsche’s philosophy when I was embarking upon a philosophy and english degree at university. Of course, I’d heard of him before, but like many others I had associated him with anti-semitism. The idea that Nietzsche was anything resembling national socialist is a myth, as it was his sister who edited his works after his death and geared them towards a more unpleasant direction. It is easy to see how a misinterpretation of his philosophy could be made though – the Nazis wanted to create a super-race, and Nietzsche’s ideal of the Ubermensch (which can be translated as the ‘Superman’) may, on a superficial reading, be construed to be aimed at the same end. The ideal of the Ubermensch, however, was aimed as an attitude towards life. Along with his ideal of the Eternal Return, it is a way of living life, a way of being able to affirm life (I would like to point out here that the Ubermensch can be a concept applicable to women as well, even though at the time the concept was thought-up it would only have been applicable to men).

The Ubermensch attitude towards life allows one to take on the burden of one’s past experiences and redeem them, as will be discussed in further blogs relating to the Eternal Return. The Ubermensch is “Master of himself” (Hollingdale, 2003. His emphasis), not the master of others. In self-overcoming an individual gains power over him/herself. Nietzsche claims that having mastery over the self is much more powerful than having mastery over others. True power lies in self-mastery, and thus the Ubermensch, who is master of him/herself, is the most powerful individual. Therefore, Nietzsche’s philosophy lauds the emotionally strong rather than the physically strong, although he claims that those with the Ubermensch attitude, through attaining self-mastery, would be the healthiest and happiest of individuals.

A facet of Nietzsche’s philosophy that I cannot agree with, however, is the notion of there being no teleology outside of ‘human nature’ to which our lives should aim. He claims that through self-overcoming we should just become, as an over-riding teleology towards which we aim would be far too constricting. It was not uncommon during the Enlightenment (c. 1600-1850) for philosophical theories to evade or completely deny the importance of teleologies. Science had begun to answer questions that religion could no longer explain – if the movements of the planets could be explained non-teleologically (i.e. God was not moving them) then so could human beings. Thus, where religion was rejected, so was teleology. Like other Enlightenment philosophers, Nietzsche explained moral values non-teleologically by identifying features of human nature to justify them against. He does this by claiming that it is human nature to pursue the gaining of power, and thus anything which prevents individuals from gaining power over the self is ‘bad’, whilst that which is involved in gaining power is ‘good’ (Twilight of the Idols, p. 127-128).

However, surely the point of morals is that we try to overcome our subjective perspective of the situation in front of us by applying some over-riding framework separate to our human nature (and by this I do not mean some kind of religious doctrine), an example being that I might be looking forward to going out to the pub but a friend calls me in tears needing to talk just before I leave the house and asks if she/he can come round for the evening – I want to go out, but I value the feelings of my friend so I forego my plans and stay in to comfort her/him (I value the feelings of my friend as part of a framework of what type of person I want to be, separate from my human nature). It is possible to will the Ubermensch attitude into existence as part of a teleology of what type of person you want to be – gaining mastery over the self (and thus one’s past) is inextricably tied up with your relations to other people because in creating a future for yourself that could justify your past you must have some sort of idea of what sort of person you want to be, and that involves how you would help people other than yourself when they are in need. This is something which Nietzsche does not take into consideration (I would not have wanted to be the type of person who left my friend in tears whilst I went out and had fun, because it would have been cold and cruel – I want to aspire to mastery over myself but I cannot affirm a life in which I did not help my friends when they needed it, and life-affirmation is one of the main purposes of the Ubermensch). I will elaborate more on my views upon the Ubermensch attitude in future posts.

Therefore, in relation to moral issues, you may find me taking more of a Contextualist perspective rather than that derived from the Enlightenment period.

No comments:

Post a Comment