Thursday, 19 June 2008

Metal and rock genres and male sexual privilege...

I had never really given much thought to the portrayal of women in music genres other than pop music, because it is that particular genre that has always made my blood boil somewhat. Watching scantily clad females ‘bopping’ around a stage singing about ‘love’ (a very narrow definition of love I might add) is not my idea of fun. It gives the impression that for a man to ‘love’ a woman (i.e. want to have sex with them), women must be attractive. I remember a television interview with The Pussycat Dolls – when asked what their image was all about they responded that they are all about ‘looking good’ and ‘being seen with the right people’. Am I the only person to see the shallowness in this? They are perpetuating the notion that women are only valued on how they look. And don’t think they are the only group to pass along that message.

When in Sainsburys the other day, I glanced at the magazines in the vain hope that maybe they stocked the music magazine Terrorizer. Suffice to say they did not. What they did stock however was what must have been about twenty different women’s magazines all stating that they have the answer to female problems. These problems are not life-threatening, although you would think so by the way they are talked up. These problems all relate to a woman’s appearance. How to make one’s hair shine, how to apply make-up evenly, how to have a flatter stomach this summer, how to lose weight (that’s the most popular one), how to have an even tan, the latest cosmetic surgery treatments. And those are just a few! Nowhere does it say that make-up IS NOT necessary, nowhere does it say that women do not have to aspire to a thinner figure.

Germaine Greer was not wrong when she claimed that “Every woman knows that, regardless of all her achievements, she is a failure if she is not beautiful” (Greer, The Whole Woman, 1999. p. 19). One only has to take a look at programs such as 'How to Look Ten Years Younger' to see this in action. The edition a few nights ago portrayed a woman who was fantastic at DIY. But this was somehow portrayed as irrelevant because she did not look ‘feminine’. The narrator even claimed that due to all that work her ability to use make-up had sadly been left to one side, hence putting across the prevalent notion that women who do not try to live up to ideals of female beauty are careless, lazy, and put no effort into their appearance - forget that they may spend their time engaged in other things. This sort of propaganda does nothing but place upon women an unfair pressure to look a certain way and be a certain way. The ‘contestant’s’ friends and daughter even paid little attention to her DIY abilities, focusing instead on how that ability had scuppered her chances of looking attractive. But don’t worry, Nicky Hambilton-Jones was there to help. The very same woman claimed a couple of weeks ago that she doesn’t “believe in feminism. Being sexy is one of a woman's biggest assets. To downplay that is madness. I don't want to compete with men. I want to play on my strengths while they play on theirs - and let's see who wins.” (see whole interview here). It makes me want to scream!

So now I ask the questions What does being a woman entail? What is being a woman like? What does it mean to be a woman? These are all questions appropriated by advertising that more or less propounds a message that scratches the surface yet claims to be exhaustive – being a woman, for such advertising, means being concerned with the condition of her hair, or the tone of her skin, the smell or hairiness of her body to a much more obsessive degree than males. And yes, I do mean obsessive. Women are conditioned from birth to be overly concerned with their appearance. Germaine Greer puts it wonderfully when she claims that whilst BDD (Body Dysmorphic Disorder) “is pathological behaviour in a man”, it is “required of a woman” (Greer, p. 20). One only has to look at toys aimed at girls to see that women are primarily valued by how they look. Dolls where girls can primp and colour the hair and apply the make-up are nothing more than a practice for adult life that is increasingly becoming earlier and earlier for girls who are coerced into thinking that wearing make-up is something ‘natural’ that all women do, that it is part of being a woman. It is the toys and advertisements that do the coercion, portraying all the ‘popular’ girls as those who wear make-up, and by ‘popular’ I mean ‘popular’ with boys. Everything seems to convey the message that the point of a female’s existence is to cultivate one’s appearance so that men will find them attractive.

Being a woman entails in many senses being the lesser sex – ‘lads-mags’ portray this message perhaps the most comprehensively. Homogenous, airbrushed, flat-stomached women arranged in increasingly provocative positions, tagged with the words ‘Take her to a motel room and bang her like a beast’ (Nuts, July 2006 – more quotes here under the leaflets section). Women are always the ones being enjoyed – even when the female is in a sexual position deemed more under a woman’s control, it is the male’s pleasure that is focused upon. ‘Lads-mags’ are widely available in newsagents and they all portray the message that women are there to be enjoyed. Even more disturbing is the suggestion that women like a man who will ‘take control’ in the bedroom, that women are thrilled with this male-appropriated take on sex. This is where notions of ‘she’s playing hard to get’ come in. Ideas like this ensure that some men believe that ‘no’ does not mean ‘no’, that it in fact means ‘please continue trying to get me into bed, I’m actually enjoying this forceful coercion’ (and, of course, the coercion may be justified later by the male claiming that it was ‘just a bit of fun’, something which usually gets the offender off the hook as the phrase implies ‘shared knowledge’ amongst men, and thus is a method of trying to get other men to see his point-of view). The woman’s ‘voice’ is not taken into consideration unless, of course, it is moaning in pleasure at the controlling man.

This is all nothing more than evidence of an insidious male sexual privilege that men and women are conditioned into from birth. Men think they have a right to sex, and it is women who are expected to provide themselves for it. Think about it – when in a relationship men expect that they will get sex. If they don’t get it, they look somewhere else for it under the innocent line of ‘this relationship isn’t working out’. A woman’s explanation for why she might not want sex at that particular point in the relationship will, in essence, fall on deaf ears. There is an unspoken number of weeks whereby a man can expect his girlfriend to ‘put out’, and if that number of weeks is not met then the relationship is over. This may sound somewhat melodramatic, but it is true. It is incredibly telling how defensive men get when women point out to them this notion of male sexual privilege. It is almost as if they want us to shut-up just in case any other women overhear and also realise it to be true. I'm not, of course, suggesting that women don't enjoy sex. A lot of women do. I'm just pointing out the expectations that males place on us when it comes to sex.

The above is why the blog I linked to at the beginning is so interesting. Women in the rock and metal genre are expected to be more forthright. I have never met a woman into metal that likes the portrayal of women in generic lads-mags such as Nuts or FHM. Yet, many will wear ‘gothy’ lingerie on an Ann-Summers theme night or in a bikini contest (on a side note, I remember when being a goth meant showing as little skin as possible, but then again I’m confusing being a goth with being into rock music).Wearing these clothes are not for the women’s benefit. They’re deceiving themselves if they think it’s a sign of women’s liberation. It is just perpetuating the notion that to get any attention from men, women have to fit into a narrowly defined ideal of female beauty – in this case the ideal is different to the mainstream as it requires more of an edge (spikes, dark reds (because it’s the colour of blood?), blacks, metallics), yet the ideal is still prevalent throughout the ‘rock scene’. Thus male sexual privilege is at large within the ideals here as well. When I say that such women are expected to be ‘forthright’ I mean defined as having a loud voice, willing to act violently, and swearing a lot. Personally, I would prefer women to be forthright in the sense that they are able to put across a rational view forcefully rather than shouting violently any old nonsense.

Being loud is not going to liberate women – if anything it’s just the masculinisation of women. Germaine Greer beautifully describes a vision of womanhood that is not subject to a male perspective: “[A] woman who [does] not exist to embody male sexual fantasies or rely upon a man to endow her with identity and social status, a woman who [does] not have to be beautiful, who could be clever, who would grow in authority as she aged” (Greer, 1999. p. 5). Now this is an ideal that could be relevant both across the mainstream and the rock and metal subcultures – women as no longer valued on how they look, but for their intellect and strength of character.

Tuesday, 17 June 2008

Grief, or rather the lack of it...

“We have explicit expectations of ourselves in specific situations – beyond expectations; they are requirements. Some of these are small: If we are given a surprise party, we will be delighted. Others are sizable: If a parent dies, we will be grief-stricken. But perhaps in tandem with these expectations is the private fear that we will fail convention in the crunch. That we will receive the fateful phone call and our mother is dead and we feel nothing. I wonder if this quiet, unutterable little fear is even keener than the fear of the bad news itself: that we will discover ourselves to be monstrous” (Lionel Shriver, We Need to Talk About Kevin, p. 92).

I have never thought myself to be monstrous, but it is easy to see why people would think I am as I’ve uttered the unutterable – I do not feel anything when relatives die. Do not think that I am completely without sentiment or that I’ve not latched on to some integral part of life – I understand that I am expected to grieve, expected to be sad. I even expected myself to be melancholy when my grandparents died. But the most sadness I felt was directed towards my mother because she was sad and I could not understand why I was not. I am told that sometimes it takes months or years for the death of someone close to really settle in and grieving to begin. I guess I’m still waiting.

Grief, to me, is the melancholic expression of loss. It is a melancholic reaction to a certain void, a lack, a space that has suddenly opened where the deceased once was. I cannot understand this. Surely when a person dies, the immediate first step should be to celebrate that person’s life? Instead of ‘mourning’, why not consider all the things the deceased accomplished in his or her life and perhaps think about how their take on life matches up to your own. Death is the perfect time to consider whether your principles are ones that will give you the opportunity to live a worthwhile life because it is perhaps the most significant reminder that we are all going to die one day.

There is an aspect of the language of death that strikes me as awkward. People speak of their relatives as looking down on them as if they are some kind of omnipresent entity. Am I the only person who finds this notion disturbing? Relatives would not only look down on you when you’re doing something that would make them proud like winning a rowing contest or passing a degree, you could not pick and choose what they look down on. They would look down on your most sordid moments and your most unpleasant moments. So although the notion of omnipresent relatives may be a form of relief to some people I would find it somewhat constricting if it were to be true. Of course, I cannot rationally believe it to be true. Because I cannot conceive the mind and body to be separate, I cannot rationally believe that the mind survives after the brain dies. When the brain dies, so does consciousness, and that is the end. Yes, it’s a difficult concept to grasp because we have such a strong sense of self, but because I know that death will be the end of ‘me’, the ‘I’ that constantly recreates itself throughout life, I feel an urgency to make sure that my life is one which is worthwhile.

Tuesday, 3 June 2008

A Bit of Background...

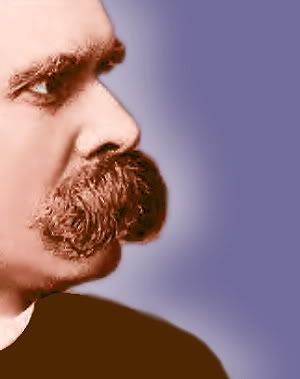

I first discovered Nietzsche’s philosophy when I was embarking upon a philosophy and english degree at university. Of course, I’d heard of him before, but like many others I had associated him with anti-semitism. The idea that Nietzsche was anything resembling national socialist is a myth, as it was his sister who edited his works after his death and geared them towards a more unpleasant direction. It is easy to see how a misinterpretation of his philosophy could be made though – the Nazis wanted to create a super-race, and Nietzsche’s ideal of the Ubermensch (which can be translated as the ‘Superman’) may, on a superficial reading, be construed to be aimed at the same end. The ideal of the Ubermensch, however, was aimed as an attitude towards life. Along with his ideal of the Eternal Return, it is a way of living life, a way of being able to affirm life (I would like to point out here that the Ubermensch can be a concept applicable to women as well, even though at the time the concept was thought-up it would only have been applicable to men).

The Ubermensch attitude towards life allows one to take on the burden of one’s past experiences and redeem them, as will be discussed in further blogs relating to the Eternal Return. The Ubermensch is “Master of himself” (Hollingdale, 2003. His emphasis), not the master of others. In self-overcoming an individual gains power over him/herself. Nietzsche claims that having mastery over the self is much more powerful than having mastery over others. True power lies in self-mastery, and thus the Ubermensch, who is master of him/herself, is the most powerful individual. Therefore, Nietzsche’s philosophy lauds the emotionally strong rather than the physically strong, although he claims that those with the Ubermensch attitude, through attaining self-mastery, would be the healthiest and happiest of individuals.

A facet of Nietzsche’s philosophy that I cannot agree with, however, is the notion of there being no teleology outside of ‘human nature’ to which our lives should aim. He claims that through self-overcoming we should just become, as an over-riding teleology towards which we aim would be far too constricting. It was not uncommon during the Enlightenment (c. 1600-1850) for philosophical theories to evade or completely deny the importance of teleologies. Science had begun to answer questions that religion could no longer explain – if the movements of the planets could be explained non-teleologically (i.e. God was not moving them) then so could human beings. Thus, where religion was rejected, so was teleology. Like other Enlightenment philosophers, Nietzsche explained moral values non-teleologically by identifying features of human nature to justify them against. He does this by claiming that it is human nature to pursue the gaining of power, and thus anything which prevents individuals from gaining power over the self is ‘bad’, whilst that which is involved in gaining power is ‘good’ (Twilight of the Idols, p. 127-128).

However, surely the point of morals is that we try to overcome our subjective perspective of the situation in front of us by applying some over-riding framework separate to our human nature (and by this I do not mean some kind of religious doctrine), an example being that I might be looking forward to going out to the pub but a friend calls me in tears needing to talk just before I leave the house and asks if she/he can come round for the evening – I want to go out, but I value the feelings of my friend so I forego my plans and stay in to comfort her/him (I value the feelings of my friend as part of a framework of what type of person I want to be, separate from my human nature). It is possible to will the Ubermensch attitude into existence as part of a teleology of what type of person you want to be – gaining mastery over the self (and thus one’s past) is inextricably tied up with your relations to other people because in creating a future for yourself that could justify your past you must have some sort of idea of what sort of person you want to be, and that involves how you would help people other than yourself when they are in need. This is something which Nietzsche does not take into consideration (I would not have wanted to be the type of person who left my friend in tears whilst I went out and had fun, because it would have been cold and cruel – I want to aspire to mastery over myself but I cannot affirm a life in which I did not help my friends when they needed it, and life-affirmation is one of the main purposes of the Ubermensch). I will elaborate more on my views upon the Ubermensch attitude in future posts.

Therefore, in relation to moral issues, you may find me taking more of a Contextualist perspective rather than that derived from the Enlightenment period.